Fact Based Journalism

Listening to OPB during their recent Spring Campaign, I first heard the phrase "fact based journalism. My first reaction was

Listening to OPB during their recent Spring Campaign, I first heard the phrase "fact based journalism. My first reaction was

My older brother, 13 months my senior, calls me every night at 6PM like clockwork. It is 9PM where he lives and he is just getting ready to go to bed. He’s able to call me using a voice activated phone. “Ann”, he says, and a second later he hears my phone ring. On the other coast, I am waiting for the sound of the ring, or looking for the screen to illuminate. When I answer the phone, there is silence at the other end. “Hi there”, I say to him. “Oh, hi” he says. And so begins our nightly ritual.

My brother was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s disease 7 years ago when he was fifty seven. He is a graduate of the University of Notre Dame and Columbia University. He is a physicist, Benedictine monk, and a Catholic priest. He taught physics and led the outdoor program for 30 years at a Benedictine inner city high school in the heart of Newark, NJ. He lives in St Mary’s Abbey in community with his fellow monks and priests who work relentlessly on behalf of the students they serve and whose lives they are dedicated to saving. “Whatever hurts my brother, hurts me” is the banner under which they live and work.

“Where are you”, he asks. While I am often at home in Portland, Oregon, I also travel quite a bit and I tell him exactly where I am. “Wow” he says. “When will I see you”, he wants to know. He says this even when I have just left him at the Abbey, and am in my hotel room 5 miles away in Hoboken. I see him quite regularly and I always tell him when I’ll see him again, whether that is the next day or the next month.

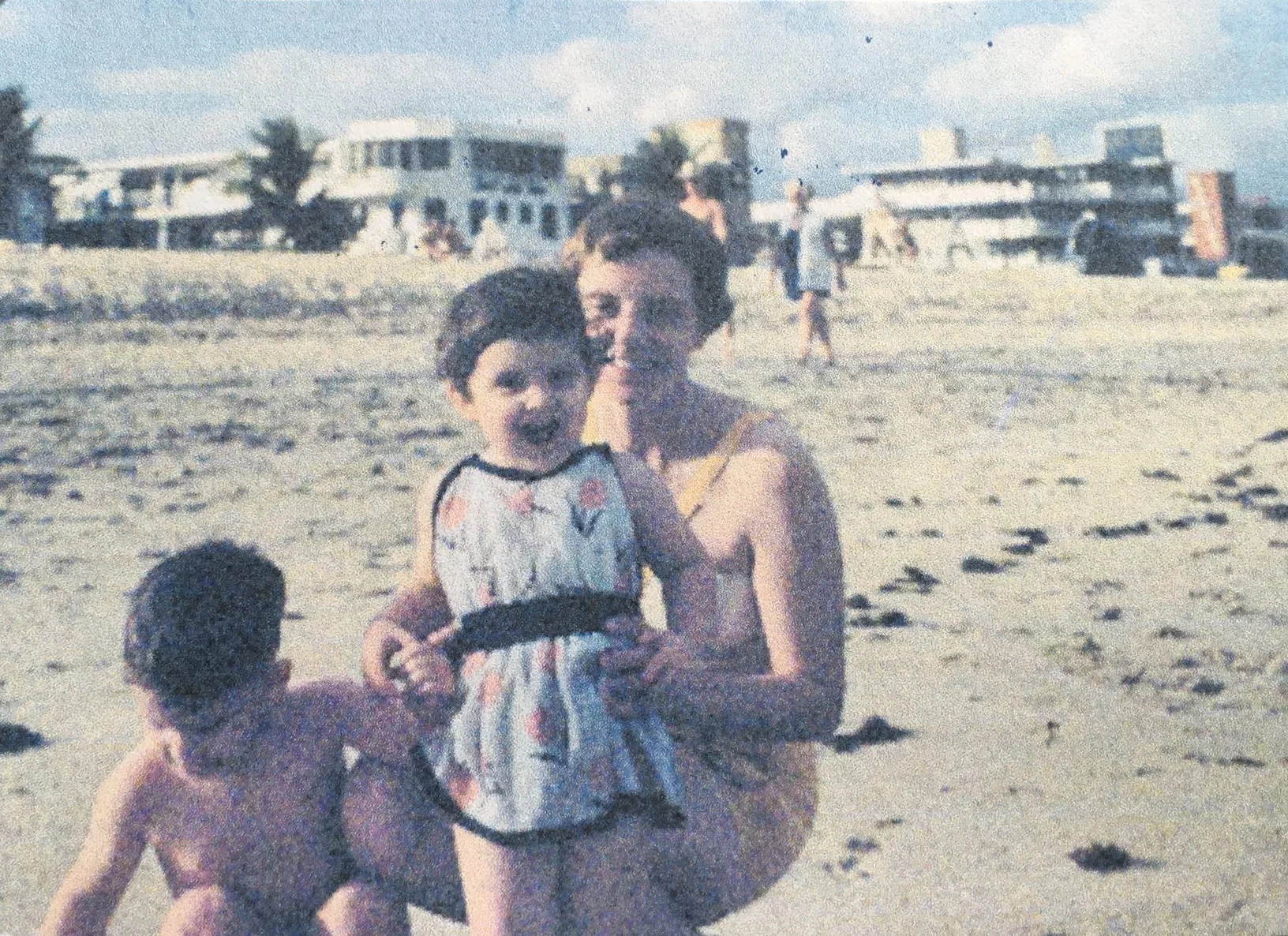

We are very, very close. He and I were number one and two in a family of 8 children, 7 of whom grew to adulthood. We were the big kids. We took our responsibilities seriously, no other option in a big Irish Catholic family. We also relished our seniority with a kind of smugness. When one of our younger sisters (a twin) said, during a bit of a fit, “You know what I wish, I wish there were only 2 kids in this family!” My brother and I shot each other a knowing glance and he replied, ”Yeah, and you know which two they’d be” to her immediate indignation, and our mutual delight.

I proceed to tell my brother all about my day, even if, perhaps especially if, it included him. He listens while I tell him details of the weather, meals eaten, trips taken, sights seen. I tell him all about our siblings and nieces and nephews. He listens and occasionally comments. Some of the time he will try and tell me what is on his mind. Recently it has been harder and harder to understand what he is saying, the words are too mixed up, the sentences garbled. No matter, it’s good to hear his voice and his laugh.

He and I were both born in Cleveland, Ohio and spent the first seven years of our lives in Canada, moving briefly back to Cleveland before landing in New Jersey. In Cleveland and Canada as our family grew, our homes did not. The “boys” (three of them) were in one bedroom and the “girls” (also three of us at that time) were in another. But when we moved to NJ, everything changed. We moved into a very large home, lots of bedrooms and bathrooms. My parents had gone ahead and set up the house and, arriving in the dark, they showed us to our bedrooms. Mine was at the end of the hall directly opposite my big brother’s room. With the door open, I could see him in bed. I was terrified. I don’t think I’d ever felt that alone. I dared not share that sentiment with our parents so I whispered, “You awake”, to which he answered, “Yes” I don’t know how many times I asked that question that night before I fell asleep, but each time I asked, he patiently answered “yes”. He was in the 4th grade and I was in the 3rd. For many weeks, this nightly ritual repeated itself until my parents decided that I should sleep in the room attached to theirs where our youngest sibling, a brand-new baby girl was also sleeping. She eventually got her own room, as did the other girls, and the boys moved to the third floor en masse. I stayed safe and sound in the room next to my parents.

“Are they taking good care of you” I always ask. “Why yes” he answers. We sit in silence for a bit and then I let him know that it’s time for him to go to bed and sleep. His caretaker is there to help him. “Sleep tight”, I tell him. And then, with unwavering clarity, he ends our communication in the exact same way, each and every call; “Good night, God bless, much love”, he says. “I love you” I say and hang up.

Life is perhaps a big circle, launching out and doubling back. I believe this now, as I answer his call, which I hear as a whisper across the threshold of two rooms at the end of a long dark hall at night. But now, it is he who, in a different shade of murkiness and fear asks: “Are you there” and I say in return “Yes”.

(Written February 2016. My brother died Sunday, July 10. He had stopped calling in April.)

Before I forget......

Here’s the thing, my families genes run thick with forgetting. Not everyday, garden variety forgetting but the long, slow kind of forgetting that ends with knowing no one and losing track of how to live.

We’re also Irish, and deeply connected to the Blarney Stone. We love to hear and to tell a good story. Often a good story is one not necessarily constrained by actual facts. I’ve been wondering lately if this is a curious mutation in our remembering gene. If the stories we tell of our lives are rich and compelling in spite of this lack of attention to detail, is actually forgetting the details so bad. No and yes. It’s a short run, long run kind of equation.

In the short run, the habit of telling stories; funny ones, sad ones, scary ones, ribald ones, lets us fall into the easy rhythm of being wrapped up together again in the feelings and emotions of times past. The lively exchange of different “rememberings” of a shared event make the experience even richer. This is what we do, we Irish. We embellish, we extrapolate, we editorialize, we catch the slipstream of a good “telling” and ride it all the way home, falling into the arms of our listeners who travel willing with us because it just feels so damn good. We laugh, yes most of all, we laugh. It is said that if you’re Irish almost everything is eventually a funny story. Almost. And so, there it is, the little bit of forgetting, and the little bit of creative license each time a story is told and re-told. Otherwise, our wisdom goes, it would be incredibly boring, the telling of exactly the same story over and over again.

But then, in the long run ,there’s the real forgetting. Forgetting who it is that’s telling the story and how you are connected. Forgetting any reference to time and place. Forgetting names, including your own. Forgetting your past, and your present. But, on the path I have travelled with my mother, and am on with two of my brothers, down the long road of dementia, the ability to laugh out loud, and to cry soft tears, when listening to stories continues. It is, perhaps, our longest, deepest, remembering. It’s our music. It reaches all the way back to the generations of story tellers from which we came, and the blessings that all those stories bestowed upon us. Our stories are the grace that holds us together, even when the remembering of language fails. It’s the cadence and the lilt and the rhythm and rhyme of our lives.. And in the end, our last words may be unintelligible, except soul to soul. And so, we continue to tell.

I don’t know what my own long run will be, but I feel compelled to write down some of my stories. Don’t bother fact checking them, just come along for the ride. Hopefully they’ll strike a chord. Maybe you’ll write down of few of your own. After all, the forgetting thing catches up to all of us, and this way your life’s adventure will be....remembered.